Prologue

The opening pages of The Third Solitude

As I arrange the publication of three interviews over the coming weeks, I wanted to follow up my announcement of this site’s revival with something for you to read in the meantime.

It has been three and a half months since my book, The Third Solitude, was published. In the aftermath I have had some of the conversations I had hoped would result from my reflections — on history, memory, Zionism, nostalgia, and much else — being out in the world.

I have also been on the receiving end of considerable vitriol, coming primarily from people whom I’ve long known and who, despite not having read a word of mine, insist that I have betrayed them.

It is for them that I am sharing (below) the brief prologue to my book, in which the central subject matter and philosophical concerns of the pages to follow are laid out. (I am also, of course, sharing this for those who are otherwise interested in the book, but would like to read a little of it before seeking out a copy.)

I welcome your thoughts and questions in the comments section below.

(Nota bene: I have had to make some formatting changes for this post. I preserved the original spacing and section-breaks as best I could. The Third Solitude: A Memoir Against History is published by Dundurn Press. Copyright Benjamin Libman. All rights reserved.)

WHAT THOU LOV’ST WELL SHALL NOT BE REFT FROM THEE

“His sufferings were unspeakable. Here, look upon a man who was more tormented than Job!”

Who? Bontsha wondered. Who is this man?

— I.L. Peretz, “Bontsha the Silent” (trans. Hilda Abel)

Three voyagers are lost at sea. They have been for quite some time — for longer, in fact, than any of them can remember. So long indeed, that none of them knows how they wound up at sea, nor where they were trying to go.

Without instruments for navigation, they are forced to follow the stars. They crane their necks in every direction, looking for a sign. “There!” says the first traveller, pointing up and starboard. “Do you see that?”

The other two travellers shake their heads. “There,” repeats the first. “Look. I see Orion!”

After a moment, the second gasps. “Oh!” he says, pointing to the same spot as the first. “Well, I see the Giant!”

The third, following along, remains silent. The others look at him expectantly.

“So?” says the first. Silence.

“Do you see the Giant?” says the second. “Or better yet,” adds the first, “Orion?”

The third says nothing. In fact, he does see something: the handle of an adze, clear as day. But for a while he says nothing. His speech is weighed down, for they have been out there for quite some time, knowing not how they got there nor where they are going. All they know is the boat, one another, and the sea. Some part of him understands that they have always been at sea, and for all he knows always will be. And so he is silent for some time, staring at the sky.

The others think he sees Orion, or else the Giant. In fact, he sees the handle of an adze.

They look at him expectantly. “So?” the first says.

“I don’t see a thing,” the third traveller says, “except the stars.”

▣ ▣ ▣

I wonder what it is like to see the stars, rather than Orion, the Giant, or the handle of an adze. That is what this book is about: dissolving common patterns — resisting pattern-making habits — for the sake, simply, of seeing. What then?

The patterns I care about are characteristic of history: the grand histories of nations, but also the trifling histories of personal memory. In The Origin of German Tragic Drama, Walter Benjamin wrote that “ideas are to objects as constellations are to stars.” Many have seen it fit to extend the analogy: as history is to the past.

To connect each dot and to form from those connections images and stories is something we have always done. It is a natural human reflex, perhaps the only one possible in the face of the great sobering fact: that we are on our own, lost at sea, knowing not how we got here nor where we should point our boats. The past is our dome of stars, and despite lacking any transcendental destination we project onto those stars the signs that will give us the illusion of making sense, of following meaning, and therefore of going somewhere meaningful. But each of us should be troubled by the contingency of these images, by the fact that I see a Giant where you see the handle of an adze. The question of which of us is right gives way quickly to the disquieting truth that neither of us is.

The past tells us very little of its own accord; we are the ones who make it speak. Afraid to be alone with meaninglessness, we manufacture a voice, a chorus, to keep us company. What if, instead, we were to content ourselves with our own company, the gentle rocking of our boats, and the quiet, immaculate canopy overhead? What else might we see?

The past I am trying to see in these pages, shorn of its constellations, belongs to the world that made me and that remains a part of me. This is a world populated by Europeans and North Americans, Jews and gentiles, francophones, anglophones, and allophones; it is home to my family, friends, teachers, lovers, enemies, and acquaintances, all of whom will appear before you in some form or another. It is a world created in part by those who, like my great-grandparents, left another, older, world behind, in order to escape destruction during the last world war (or after surviving it). The first traveller in me might call it a post-Holocaust narrative; the second, a Jewish coming-of-age tale; the third, remaining mute for a while, might see a paradise lost. But, as if telling himself otherwise might change his relation to the world, he says: “I see the past.”

The parable of the three travellers was told to me by a Georgian woman in a Berlin bar some years ago. Appropriately, some doubt in me remains as to its true meaning. But it reminded me of a fragment found in one of Kafka’s notebooks: “The world will offer itself to you to be unmasked; it cannot do otherwise, it will writhe in front of you in ecstasies.” For once, channelling the third traveller, I am skeptical of Kafka’s claim. I’ve undertaken this book on the conjecture that, if we resisted just long enough, this writhing might stop, and the offering might dissolve. Because maybe the past isn’t offering itself to us at all. Maybe the writhing is all in our heads.

▣ ▣ ▣

My first, ill-advised attempt to constellate the stars came on New Year’s Eve a few years ago. I was in the Laurentians, at the house that my great-grandfather Eugene, an Austrian-Jewish refugee, had built on land he had purchased from the Quebec government for a bargain,

in the middle of the last century. Having grown up in a nature-loving part of the world, and having spent much of his youth in the Austrian mountains and woods, or fishing lakeside, with his beloved wife Anna (before all that would be taken from them), he had longed, so it is said, for the quiet and sylvan splendour of rural Canada.

My aunt was reading in the armchair she always read in; my uncle hovered at the hearth, stoking the fire. My brother Eli was typing something on his laptop at the small table in the far corner of the room, his face illuminated in a bluish glow. In the kitchen, those preparing drinks for themselves were listening to bolero. There were still five or six hours until midnight, and I had just resolved that I would write the story of our family.

I would explore in that story some home truths: what it means to be disfigured by suffering, to be flattened by ill fortune, yet to go on living as if one had merely drawn the wrong lot — as if good fortune, equally likely, lay just over the horizon. If only one kept living for it. It is the subject of the book of Job, and of the famous I.L. Peretz story in which a man named Bontsha, who remains utterly silent and without complaint as he endures the slings and arrows of fate before his death, is too meek even to ask for his due reward when he is offered it, unconditionally, in Paradise.

Nor were these themes exclusive to literature and scripture. I had inherited them from teachers and community elders, from institutions, individuals, parents, cousins, friends, ghosts, folk tales, old saws, and old jokes. From a packet of letters, administrative documents, and a few photographs belonging to people I knew from family histories but had never met. I knew them the way I know Odysseus and Oedipus, characters who recur across tales and tellers, always with a difference, yet always bearing a set of persistent, inalienable qualities, characters whose actions live somewhere between the imperfect and conditional tenses — what they would do then or would do now.

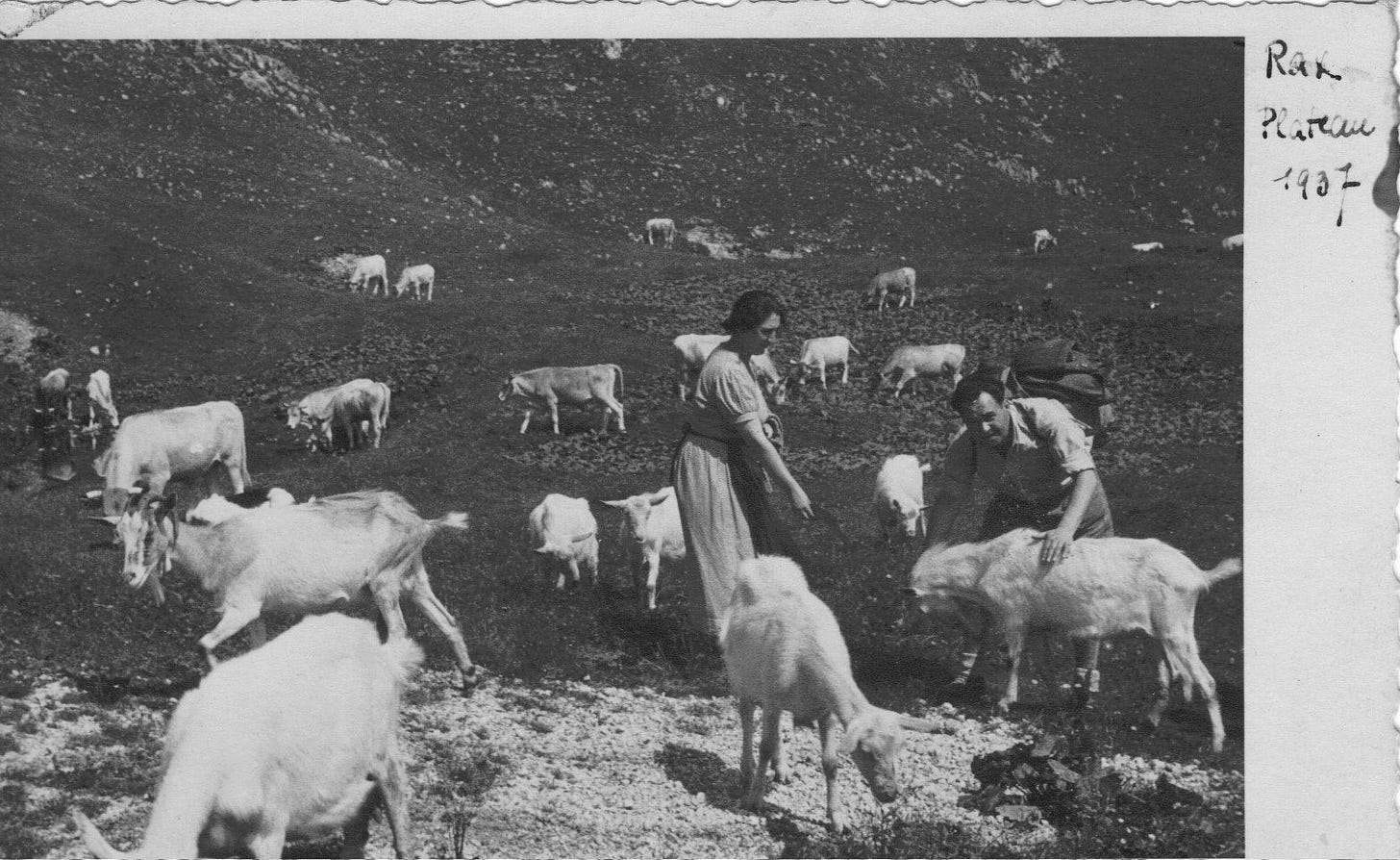

Henry and Jetka, pictured above at a wedding, were two such characters. Their stories — that is, their suffering, their lot, their inalienable qualities — had become lore long before my birth. As I fantasized about my family story, I hadn’t understood this as a problem. But it was, and it remains so. Not a problem in ethical terms, but in epistemological ones. Legend and history both interfere with the past. Most of all, they interfere with each other: like oil and water, they cannot be assimilated. They can, at best, be suspended one within the other, a slurry of stubborn isolates.

I have been told many things about Henry by many different members of my family. They don’t always line up. I could see this as strange for a matter of fact: a thing either was or wasn’t; a man either did this or that. But when you compare accounts on any human subject you find that the differences have less to do with verifiable data than with the comparably more fluid matter of relationships. Henry was Eugene’s brother. He was my grandmother Eva’s uncle. He was great-uncle to my father, his siblings, and many of his first cousins. What is at stake for each of these people when they tell you about Henry is their relationship to him; the truth that matters is the truth that obtained between them. This is the truth that gets recorded in memory; dates, facts, and figures are as if incidental, sometimes brought into alignment thereby, not the other way around.

What I will tell you here is also a certain kind of truth. When as a young man, Eugene moved to Vienna, Henry moved to Lemberg, the capital of Galicia, now Lviv. There he married Zina, and the pair had a daughter, Theresa, known to all of us as Tecia. They also had a son, Richard. Then, as always, the war. I will tell you later how Eugene managed to get out of Austria while the getting was good. But we’re talking about Henry now. Henry, Zina, Tecia, and Richard were sucked into the vortex. Richard, just a child, was sent to hide among Christians; he was found, at some point, and murdered by an SS officer. (“It wasn’t something talked about much,” my father tells me, in the passive voice, which is the only one appropriate to the subject matter. “We kids only knew the story because Henry had a boat that had his name on it, ‘Rys.’”) Henry, Zina, and Tecia went the way of most of the continent’s Jews: labour and concentration camps. They were separated early on and, somehow, all of them survived. Henry had managed at some point to escape the camp where he had been relegated to work and die and went to live with the partisans in the forest. It is said that he forged documents, mostly passports and other identification papers. At the end of the war, he looked for his family. Today we are ignorant of the utter havoc that was finding loved ones, the formlessness of that particular panic. Tohu va-vohu, as the narrator of the Torah says. Dead or alive, each person would have to be traced (hence the name of the agency to which Henry appealed, the International Tracing Service), their movements mapped to ghettos, camps, train cars, mass graves, and death marches across mainland Europe. This took time, but it was done. It took even more time if the people being sought had died or survived behind what was now the Iron Curtain. By the time Henry found out that the two people in the world most important to him were alive in Eastern Europe, he was already in Canada, where he had been reunited with his brother, Eugene. He was already trying to live life again, having suffered life’s iniquities. He who, like all the Jews he had known, had been more wronged than Job. He was already married again, to a woman named Stacha. At the time the above photograph was taken, he was still married to Stacha, and despite knowing that Zina and Tecia were alive and well, he had yet to be properly reunited with them. It was his niece Ada’s wedding. And rather than join the procession with his wife, he did the menschlich thing and walked arm and arm with Jetka, Anna’s sister (and so Eugene’s sister-in-law). Jetka was, in the above photograph, a widow. Like Anna, she had come to Canada

just before the war, and after it was over had agreed to marry a man whom she did not know, a man named Ignatz, who had lost everyone he had known and loved, and whom Eugene and Anna wanted desperately to help emigrate to Canada. Jetka had married him for a visa; they fell in love nevertheless, or so certain letters between them attest. He was dead within a decade. Someone may someday write their story.

When Henry was reunited with his wife Zina and his daughter Tecia in Montreal, in 1967, he was in the eyes of Jewish law polygamous. His first wife and daughter moved into the spare apartment of the duplex where he and his second wife, Stacha, lived. Together, having suffered what needed to be suffered, they seemed to have decided to suffer no longer. Rather than quarrel, they coexisted. They lived one on top of the other, dined and travelled together. Surely there’s a Jewish joke out there about a man whom the Lord has decided should have not one, but two wives.

▣ ▣ ▣

The book you hold in your hands is not the story I rather sophomorically resolved to write a few years ago. I did write it, a fictionalization of Henry’s postwar life, and it sits somewhere in the cloud. But in exorcising my subject I discovered that something vital remained within me. What was past, that is, what had really been and what had really happened, remained unattended to. I thought that I ought subsequently to work on a true account of who these people were and how they lived. But this too, of course, was a fiction. All of history is a fiction, an Orion or a Giant. If we can agree on the events, we have no way of relating them one to another without some invention of our own. The sun has risen every morning and has set every evening, as Hume pointed out. But we cannot deduce from abstract law that it will do the same tomorrow. We build inference upon inference, and suddenly we have told the story of the past. But something besides remains, for the past will never be exhausted by our exertions upon it. It refuses the way an object refuses.

This book is a meditation on the past that persists: the Henrys and Jetkas who remain fundamentally unknown, impenetrable obscurities, arm-in-arm, treading the soft carpet, smiling forever before the lens; the experiences, regrets, hopes, disappointments, vacillations of feeling, flutters of happiness, dreams, and fears that we can never touch, only represent. All of it so much air escaping to the wind. If I have not stopped fictionalizing, I have stopped trying to exhaust. Something vital remains, cold and unspeaking as a stone. Do not strike the stone, so the cautionary tale goes, though water may pour forth thereby. Speak to it — softly, gently, inaudibly. Speak to it without words.

▣ ▣ ▣

I realized some time ago that the black hole is the only appropriate metaphor for the ways in which we approach ineffable experiences. The experience itself admits no light; it is unrepresentable. But ringed around it is a shimmering event horizon of language, of the words those experiences have not yet swallowed up and made unavailable to us. The greater the weight that experience has in our culture — death, loss, epiphany — the greater the horizon that attends it. How many paeans have been sung to Love? And how many of these has Love not outstripped?

There is a black hole at the centre of this undertaking — a book about the forces of place, time, and character that formed the world and the generation into which I was born. I did not know what it was until I finished writing, but it will be plain to all who traversethe pages that follow. Its pull will be felt. The words that ring around this gravitational collapse will be familiar: Zionism, Israel, the Jewish homeland, war, catastrophe, resurrection. The passage of time. In addition to being real words denoting concrete things, they are also the symptom of the yearning, disordered soul within many a heart. The experience they attempt to index, when they are not weaponized in support of war or occupation, runs right through a people’s history, swelling here to an explosive point, subsiding there to an inaudible lull.

The generations spanned in these chapters have tracked the movement of this feeling, which is another way of saying that what Israel meant then is not what it means now. The Jerusalem we have invoked at the end of our Passover seders since the Middle Ages, the Jerusalem of “next year in Jerusalem” and of the Diasporic condition that has been at the centre of Jewish life since the eighth century BCE, when we were taken into Assyrian captivity, is not the Jerusalem of the Zionist Congresses, nor that of 1948 or 2025. Two thousand years of exilic culture — marked, to be sure, by occasional homecoming for some — could not easily assimilate the prize against whose lack it had defined itself.

“They produced the miracle of Israel,” is how my greatgrandmother, Anna, put it in a letter to her sister-in-law. Words whose meaning is foreign to me; I am incapable of looking at Israel today and seeing a miracle; I am incapable of looking at Israel today and feeling anything but shame. But I have to attend to her phrase, to the word “miracle”: a vague word, belonging to the vocabulary of the event horizon, a reach exceeding what can be grasped, a leap into the vapour of the metaphysical. She, who could never have imagined such a reality, had no language adequate to her awe. (Just as I would be mute in her place.) All the more reason for her to go on trying to capture it, in letter after letter. “I don’t think it is possible today to fully understand the meaning of the state of Israel to that generation,” my father said to me recently. “It is possible to understand in theory, but not the emotion. I often looked at my grandparents and thought, how can they even get through a single day? Where did they put all that sadness? Because I never saw it. Except once, with my grandfather, at Yad Vashem.” He was referring to a time when, as a thirteen-year-old, he went with Eugene on a trip to Israel. They visited the National Holocaust Monument, which was not even twenty years old at that time, and which I would visit myself a few decades later under very different circumstances. “I think we stayed for twenty minutes, then he made some excuse why we had to leave.” My father didn’t know whether Eugene wanted to leave because it was too difficult for him, or because he thought the material not suitable for a boy. But in hearing this story I was reminded that, to Eugene as to Anna, the very idea of building a memorial to Holocaust victims in a Jewish state was a triumph over history — over temporality as such. It was a way of saying that, finally, they were safe from the ravages of time. The long exile was over.

▣ ▣ ▣

A month ago, on a trip home for Passover, I was telling an old friend about this book. I explained that I was revisiting some of the things we were taught as children, lifting the corners of the ideological system in which we were raised. I assumed he would get it. Like me, he had moved away from home, had sought things he couldn’t find there. He frowned. “What are you doing?” he said with great disappointment. He meant: Why would you betray your own community like that? I didn’t have an answer for him.

Whether and to what degree this book is a betrayal is not something I can determine. I can only say that I was raised by people who warned me never to take anything in this world on faith, and always to question what you were told. I have to believe that they did not exclude themselves from being subject to scrutiny. At Passover we speak of the son who does not know how to ask. His sin is not that he is ignorant but that he does not care to know. And yet he must not be abandoned — we must take his hand as we take the hands of others and lead him along. Daily, innocent people are dying as a direct result of the miracle for which Anna would spend half her life finding the right words. Is it not ours to wonder why, in the face of so much agony visited upon an uprooted and subjugated people, so many remain silent, and so many seek its furtherance? How many simply do not care to know? Give us your hands.

An entire world of collective effort, generations of it, go into crafting the attitude of a single mind. I have tried to gather that world and its generations here. This is a world, and these are the generations to which most everyone in this book belongs, including myself. If I have betrayed them now, I have not betrayed who they might yet become. I would call a statement like that credulous if it weren’t one of the oldest tenets of the faith: each of us is responsible for repairing the world. It is not an act of hate, but an act of love. And, to borrow the words of a wise and wicked son, what thou lovest well remains.

The rest is dross.

Paris, 2024

I love that phrase, "the past that persists." And the images are wonderful. Thank you for sharing this. I will indeed buy the book and a copy for my mother, a Holocaust survivor, as well.

This is extraordinary, beautiful writing and makes me want to run right out and buy the book. I recently visited Montreal for the first time and fell in love with it (in fact I'm heading there again this weekend) and I'm fascinated by the whole region - I will definitely tell my friends there about this book, I think they'd love it.